Your International Partner in Employment & Labor Law

Specialist law firms working together to provide strategic legal advice — locally, nationally, and across borders — for all your workforce-related challenges.

Who We Are

A Global Alliance of Employment Law Experts

ELLINT is a global alliance of leading law firms specialising in Employment and Labor Law. Founded in 2013, we unite over 200 lawyers across 20 countries who share a commitment to providing practical, people-focused legal advice that scales with your organisation. More than a network, we operate as one team — combining local insight with international reach to deliver consistent, high-quality counsel across jurisdictions.

Meet our peopleWhat We Do

Smart, Strategic HR Legal Support

We help businesses navigate the full spectrum of employment law challenges — from day-to-day HR guidance to complex cross-border restructurings. Our members collaborate seamlessly to deliver consistent, commercially minded solutions that align workforce strategy with business goals.

Explore our servicesHow We Help

Helping global businesses manage their people with confidence

We advise on European Works Councils, collective bargaining, compliance, restructurings, and executive terminations across jurisdictions. We also support global companies expanding or investing in Europe with tailored employment frameworks and ongoing legal counsel. Our clients span sectors including finance, tech, manufacturing, transportation, and healthcare.

✓ Advising on European Works Councils, collective bargaining, and workplace regulations ✓ Managing employee transfers, restructurings, and acquisitions across jurisdictions ✓ Drafting Master Employment Agreements and harmonised HR policies for multinational workforces ✓ Supporting the dismissal of executives or teams in compliance with local laws ✓ Guiding companies investing or expanding into Europe on employment compliance ✓ Offering ongoing legal counsel to global businesses in fast-moving sectors

What We Share

Perspectives That Shape the World of Work

Stay up to date with the latest legal insights, firm news, events, and accolades from our team — sharing knowledge and perspectives that help shape the future of work.

Poland sets the standard in document digitalization

No Notification, No Valid Dismissal: EU Ruling Raises the Stakes for Employers

FIXED TERM CONTRACTS: Poland-Mexico

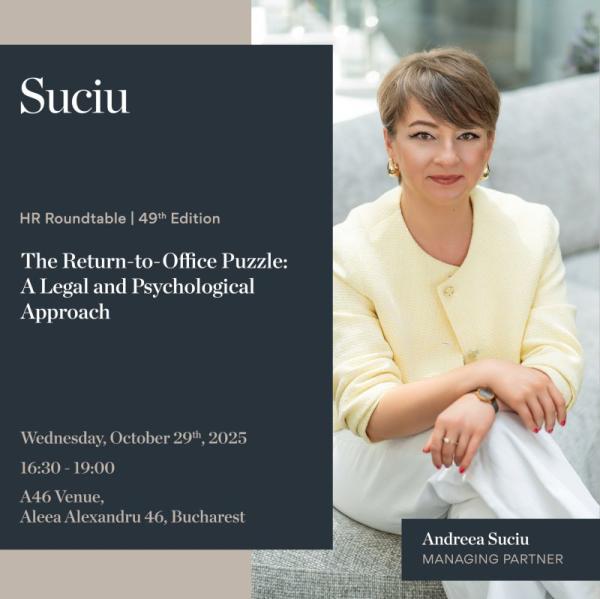

Suciu – Employment and Data Privacy Lawyers HR Masterclass

The Irony of Self-Checkout in Mexico: The Customer as an Unpaid “Worker”?

The Limits of Termination: Legal Protections for Employees in Denmark and Italy

What They Say

Voices from Those Who Know Us Best

Our clients and peers share what sets ELLINT apart — trusted relationships, deep legal insight, and a collaborative spirit that crosses borders and builds lasting partnerships.

Baohua Law Firm’s team ‘have a good understanding of foreign companies’ management and cultures, as well as their needs.’

CHAMBERS ASIA-PACIFIC | 2020

Doyle Clayton’s team is a “renowned group of individuals with an enviable reputation as specialists in the field”. “The team are personable, technically extremely strong and will go more than the extra yard for their clients. Alongside of that, their industry sector knowledge and experience is uniquely broad and deep. They are a true ally and their advice is always commercially balanced.”

LEGAL 500 UK | 2021

“Baohua Law Firm is a specialist employment law firm with well-recognised expertise”. “Their core strengths are that they are familiar with multinationals’ culture, internal processes and management practices. They have good business sense and practical experience, and their solutions and recommendations are effective and can be implemented.”

CHAMBERS ASIA-PACIFIC | 2021

Market sources are quick to highlight McInnes Dunne’s “strong offering” in the employment law space.

CHAMBERS EUROPE | 2020

‘Responsive’ employment law boutique MGG Legal ‘provides practical solutions’.

LEGAL 500 EMEA | 2019

Doyle Clayton is “the country’s leading specialist law firm in employment”

LEGAL 500 UK | 2020

Doyle Clayton is a “high-class outfit with breadth of experience”. Its lawyers are “brilliant – always responsive, reliable and practical in their approach” and “knowledgeable and very experienced in their field; they are excellent”.

CHAMBERS UK 2021

Mette Klingsten ‘has experience in a range of matters spanning the negotiation of collective bargaining agreements through to the litigation of discrimination cases.’

CHAMBERS EUROPE | 2019

Zawirska Ruszczyk Gąsior provides full-service employment law advice. Very strong, professional team and easy to work with. Their work is always completed to a very high standard.

LEGAL 500 EMEA | 2020

Interviewees particularly highlight Adam & Bleser’s work on behalf of employees in litigation, with commentators reporting that the team is “reliable” and provides “good technical points.”

CHAMBERS EUROPE | 2020

Sotra’s team is “proactive, responsive and always available.” Clients admire the flexibility of the lawyers, in addition to their “deep knowledge of the social legislation.”

CHAMBERS EUROPE | 2019

Lexellent are clever, highly pragmatical and always open to give the best advice to avoid unnecessary risks. Excellent and up-to-date command of the national labour law. Able to compare national legal requirements or actions with international ones. Excellent and modern communication skills and style. Highly efficient and confident in managing court hearings.

LEGAL 500 EMEA | 2020

Sotra’s lawyers have a lot of experience and knowledge in labour law.