The most recent data from the Natinal Household Income and Expenditure Survey (ENIGH in Spanish) has already been the subject of several analysis regarding the improvement in Mexican incomes. Generally speaking, it is hard to deny the government credit for this achievement (setting aside the ongoing debate over public transfer income, which warrants a separate discussion). As a matter of fact, both mexican men and women are earning more under the Fourth Transformation political movement.

However, there is one angle that seems to have received little attention from this biannual survey which is a structural symptom of the Mexican labor market – namely, the penalty placed on paid work for women, particularly regarding mothergood. Given how persistent this problem is, perhaps we should consider whether we are framing this issue incorrectly. Here are some compelling data points:

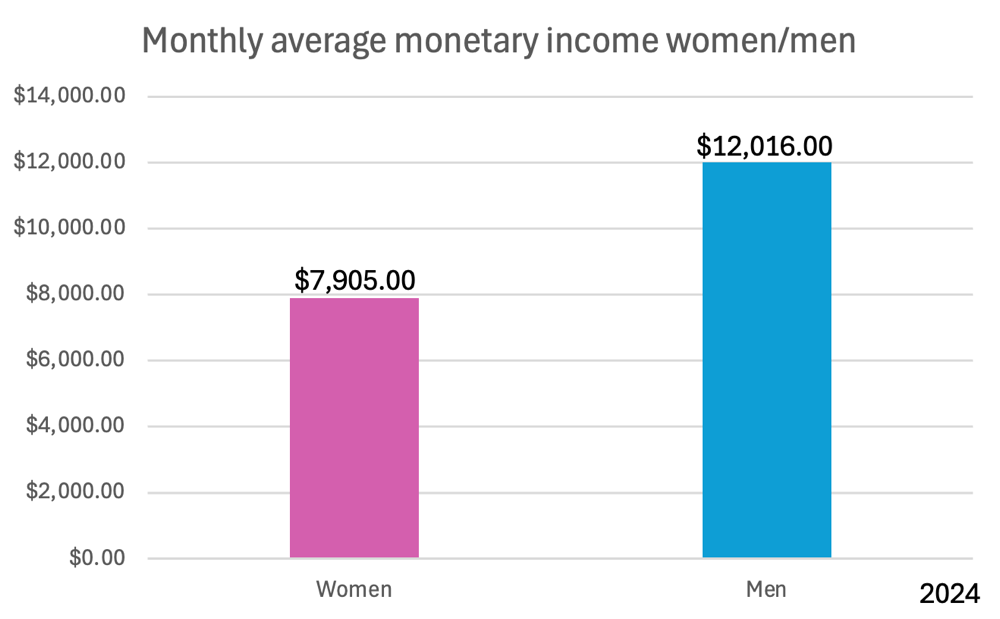

The average monthly monetary income of men is 4,000 pesos higher than that of women; in other words, women earn 52% less than men on average.

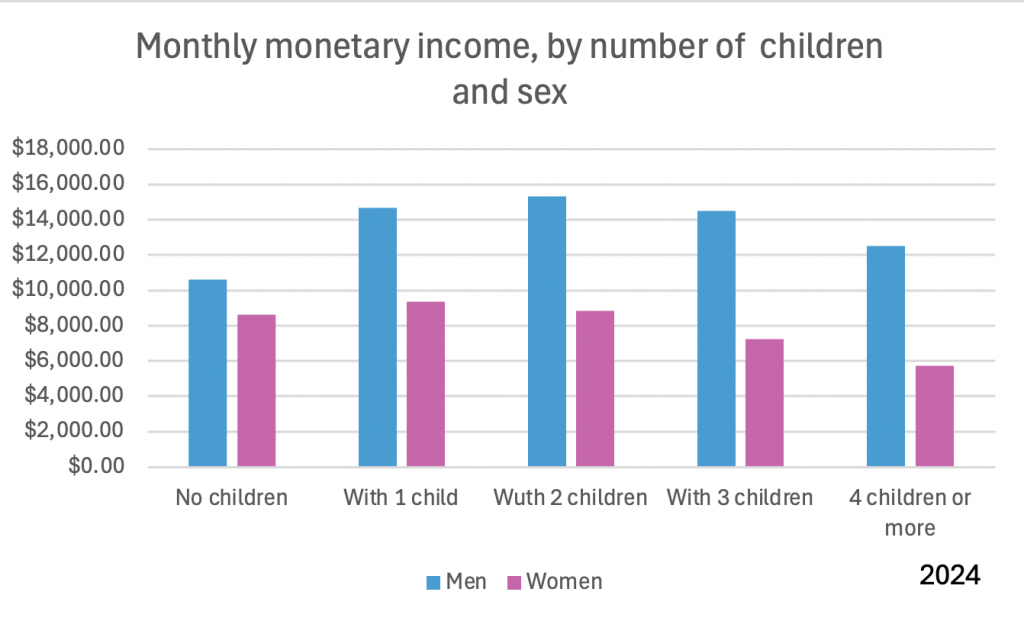

Motherhood affects women’s income: at first positively, but it declines with each additional child. According to ENIGH, a woman with one child earns more than one with none—$9,342 MXN per month versus $8,619. But from the second child onward, her income decreases by 5%, and if she has four children, her monthly income will be 40% lower than if she had none.

Men with two children (the national average) have the highest monetary income, earning nearly 16,000 MXN per month.

It’s almost irresistible jumping to general explanations and conclusions when evaluating these three facts superficially—discrimination in the workplace is often cited as the cause of the gender wage gap. But the root of the problem may lie elsewhere, and three deeper reasons help explain why women, even if they get paid, do so in smaller amounts: they are overrepresented in lower-paying jobs, work fewer paid hours, and experience more career interruptions.

Regarding the first point, the overrepresentation of women in low-paid roles stems from a labor market—and employers—that push women into certain professions or positions deemed more compatible with domestic responsibilities, which are often poorly paid. The numerous labor reforms passed in the current and previous administrations should take these INEGI figures seriously and legislate responsibly on issues like paternity leave, care policies, and salary transparency—measures that could help address these gaps and correct the inconsistencies of a labor market that remains not only unequal, but also precarious and informal.

As for women working fewer hours, it’s important to clarify that this refers to fewer hours of paid work. According to INEGI’s most recent National Survey on Time Use (ENUT) from 2019, women in Mexico devote 68% of their time to unpaid labor, while men spend just 25% of their time on such activities.

So what would a balanced scenario look like? The most detailed global data comes from the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), which in its Employment Outlook report states that the average gender pay gap across member countries stands at 20% in favor of men. In early 2018, Iceland—ranked the most gender-equal country in the world—and Germany (which has a gender pay gap above the European average) passed laws requiring public salary disclosure for men and women. However, while greater transparency can help compare wages, it doesn’t automatically close the gender pay gap.

AUTHOR

Jorge Sales Boyoli is one of the most influential labour lawyers in labour matters in Mexico and in the T-MEC region. An expert in negotiation and resolution of labour and union disputes, he has contributed to creating stability and labour peace with a large number of employers in Mexico, the United States and Canada, contributing to the generation of sources of work in trends such as nearshoring and outsourcing (today the provision of specialised services).

With extensive experience in highly complex labour litigation and a strategic vision in consulting, he is currently managing partner of the firm Sales Boyoli Abogados Laborales, founded more than twenty years ago and positioned as one of the leading firms and the one that best combines a deep knowledge of the Mexican market with experience in labour matters and an excellent positioning with the labour authorities.