Mexico: The Rise of Union Leadership and the Pattern of Perpetuation in Office

Part 1. Structural Pattern: “Discursive Renewal, Real Continuity”

In Mexican unionism throughout the 20th century and much of the 21st, a recognizable sequence is repeated:

A legitimacy crisis of the long-standing leader (due to age, wear, scandals, or political rupture).

The rise of an internal successor – not an external one – who presents himself as:

- Guarantor of “unity”,

- Corrector of past excesses,

- Defender of union institutionalism.

Consolidation of the new leadership through:

- Ad hoc bylaw reforms,

- Successive re-elections,

- Control over membership rolls and union congresses,

- Perpetuation in office until death, physical incapacity, or external intervention by the State.

The problem is not merely personal, but institutional: unions are designed to concentrate power, not to renew it.

Paradigmatic Cases

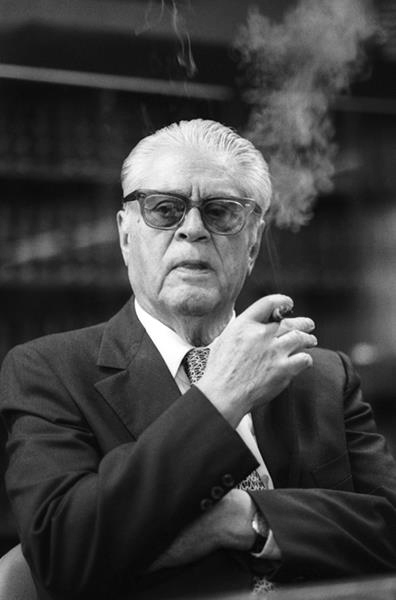

Fidel Velázquez Sánchez (CTM)

The archetype

- How did he rise? He displaced previous leaders in the 1940s–50s under the banner of “worker unity” and institutional discipline.

- Initial narrative: to prevent fragmented local strongmen and to strengthen the central labor federation.

- Outcome: Secretary General of the CTM from 1950 until his death in 1997 (47 years).

- Legacy: He normalized the idea that union leadership is neither inherited nor relinquished: he institutionalized “lifelong leadership” as synonymous with stability.

- Paradox: He came to power criticizing personalism… and turned it into a system.

Carlos Romero Deschamps (Oil Industry)

Heir who promised a break with the past

- How did he rise? He replaced Joaquín Hernández Galicia “La Quina” after his political downfall in 1989.

- Initial narrative: a “new era,” modernization of the oil workers’ union, closing the cycle of excesses.

- Outcome: He remained in office for 26 years (1993–2019).

- End: Forced resignation, not democratic succession.

- Key trait: He turned the union into a patrimonial and family-based apparatus, even surpassing his predecessor.

- Historical irony: the leader who came after the symbol of caciquismo became one of its longest-lasting cases.

Víctor Flores Morales (Railroad workers)

Silent continuity

- How did he rise? Internal displacement following the wear and loss of legitimacy of previous leaderships.

- Initial narrative: job stability in a declining sector.

- Outcome: In office for almost 20 years.

- Particularity: He did not need major discursive breaks — inertia did the work.

- A typical case of perpetuation through the absence of counterweights, not through charisma.

Francisco Hernández Juárez (Telephone workers)

The reformer who became indispensable.

- How did he rise? He displaced traditional leadership in the 1970s with a progressive and democratic narrative.

- Initial narrative: union democracy, autonomy from the State, modern trade unionism.

- Outcome: Secretary General since 1976 (almost 50 years).

- Core contradiction: a historic defender of union democracy… without real alternation.

- Even the “good” leader can become irreplaceable.

Why does this phenomenon occur?

Structural factors

- Flexible or easily manipulated bylaws.

- Controlled congresses and closed membership rolls.

- Lack of financial and political accountability.

- A union culture that confuses stability with permanence.

Political factors

- For decades, the State preferred predictable leaders over uncertain democratic processes.

- Longevity was rewarded with access, resources, and protection.

Recent change: real break or cosmetic adjustment? The 2019–2023 labor reforms introduced:

- Personal, free, direct, and secret voting,

- Contract legitimation,

- Greater formal oversight.

But:

- They did not eliminate the power of historical leadership.

- They did not impose effective limits on re-election.

- They did not change the internal culture of union power.

The system changed the rules, not necessarily the players.

Conclusion

Mexican trade unionism has repeatedly produced the same figure:

The leader who comes in denouncing perpetuation… and ends up justifying it in the name of stability, unity, or the historical cause.

As long as there is no:

- Mandatory alternation,

- Real term limits,

- And effective internal accountability,

Leadership change will remain biological or political — not democratic.